The Seen vs. Unseen: How Christ’s Agony in the Garden Makes Us Rethink Sin

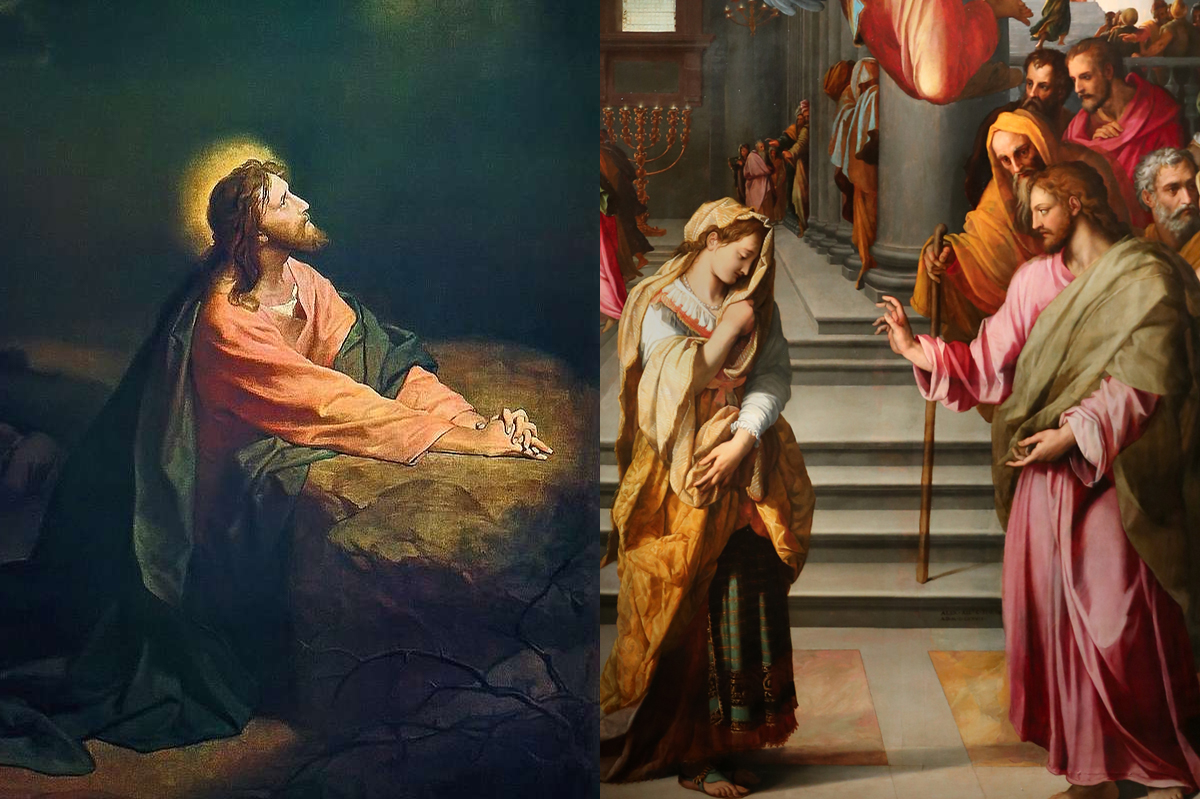

A few months ago, on the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, I was praying an evening rosary in our family chapel when the Holy Spirit inspired me to start Catholic Hangout. While praying the Sorrowful Mysteries, I began to meditate on the Agony in the Garden. As I looked to my left, I saw Christ on His knees gazing frightfully towards Heaven (we have film over our windows to mimic stained glass). The portrait of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane is faced towards our altar and Crucifix to illustrate how each of our prayers is joined with Christ’s prayer to the Father and oriented towards His death on the Cross.

As I reflected on this mystery, my attention shifted towards the writings of Pope Benedict XVI in Jesus of Nazareth, Vol. 2. “Anyone who spends time here is confronted with one of the most dramatic moments in the mystery of our Savior: it was here that Jesus experienced that final loneliness, the whole anguish of the human condition. Here the abyss of sin and evil penetrated deep within his soul. Here he was to quake with foreboding of his imminent death. Here he was abandoned by all the disciples. Here he wrestled with his destiny for my sake” (pg. 149). It was in the Garden of Gethsemane that Our Lord’s hour finally arrived and his Messianic mission would be revealed.

“And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly; and his sweat became like great drops of blood falling down upon the ground” (Luke 22:44). Upon reading the Biblical account of Christ’s Agony in the Garden, one is immediately struck by the intensity with which St. Luke expresses this event. Our Lord was in such fear that He sweat blood. The true reason for His sweating blood, Pope Benedict XVI argues, is not his fear of the Cross – rather, His fear of abandonment from the Father, which is the ultimate consequence of our sin. Many men had been tortured to death before, some in ways more gruesome than Christ. But none have experienced the radical suffering Our Lord felt in becoming sin itself and experiencing a separation from the One He is eternally begotten from.

“Jesus’ fear is far more radical than the fear that everyone experiences in the face of death: it is the collision between light and darkness, between life and death itself – the critical moment of decision in human history,” Benedict writes (pg. 155-156). His fear is profound not because it is human, but because it is divine. Christ went to the place His very nature contradicted so sinners might be rescued from the depths of their own malice against God.

Pope Benedict XVI and Fulton J. Sheen have even opined that Christ’s suffering in the Garden was greater than His suffering on the Cross, a conviction hardly calculable to the modern mind. Fulton J. Sheen writes in Life of Christ, “It is very likely that the Agony in the Garden cost Him far more suffering than even the physical pain of Crucifixion, and perhaps brought His soul into greater regions of darkness than any other moment of the Passion,” (pg. 462). In becoming sin itself, he suffered the agony of Adam and Eve in the fall, the agony of Cain’s murder of Abel, the agony of Israel’s unfaithfulness over thousands of years, the agony of Judas’ betrayal, the agony of his impending deicide, and the agony of all future sins to still be committed after his death and resurrection – in short, he took onto himself and became all of mankind’s sins across every span of time, feeling the final consequence of man’s rejection of the Father. Christ became sin in Gethsemane so we might become like Christ and share in his perpetual adoration and obedience to the Father.

Since time immemorial, Christ has always appeared incognito. He reveals Himself to the pure of heart, but his identity is kept hidden from the reprobate. Few in the ancient world expected God to share in our flesh and become a child. None expected Him to die a humiliating death upon a Cross. And of those who acknowledge the Crucifixion of Our Lord, who would dare suggest His greatest suffering came not on the Cross but on the Mount of Olives? Our Lord’s greatest suffering was not what could be seen with our eyes. His greatest suffering can only be seen with faith.

My contemplation upon these events spawned a deeper revelation into the ways we commonly perceive our Catholic faith today. Is what’s observed by the senses always how Our Lord views matters, or can our eyes deceive us? Once more, Ven. Fulton Sheen offers us a valuable insight in Life of Christ. Regarding the Pharisees condemnation of the adulteress they wished to stone to death, Sheen writes, “Our Lord here implied that He even regarded the respectable sins as more odious than those which society reproved. He never condemned those whom society condemned, for they had already been condemned. But He did condemn those who sinned and who denied that they were sinners” (pg. 256). The greater of the sins was not what was seen (adultery), but what was unseen (pride), for the adulteress had remorse and a purity of heart absent in the souls of the Pharisees, who were blind to their own sin.

This is an important takeaway for any who seek to grow in their faith, because the sins of our neighbors are disclosed to us on a daily basis. What is it that drives the news cycle but the wrongdoing of our brothers? What is it that drives social media engagement but outrage over the transgressions we think are clearly worse than our own? But who is truly the better or the worse? Only faith can judge what our eyes fail to see.

Upon this reflection, I felt Christ urge me to start this website, Catholic Hangout. The world doesn’t need another voice to condemn it. There are enough of those. What the world needs to hear is the voice of Christ. It needs to hear that it is loved. After the proud are scattered, it needs to hear, “‘Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?’ She said, ‘No one, Lord.’ And Jesus said, ‘Neither do I condemn you; go, and do not sin again,’” (John 8:10-11).

The God who became man became sin so we might be like Him and sin no more. The God who was once invisible became a God we can embrace in our arms. The God who embarrassed Himself on the Cross became exalted in Heaven so we might feel no embarrassment in our struggle with sin. The God who paid our debts defeated death once and for all so we might never taste it. “So we know and believe the love God has for us. God is love, and he who abides in love abides in God, and God abides in him,” (1 John 4:16).

I will close with one final quote from Pope Benedict XVI on the greatest love story ever told. “The drama of the Mount of Olives lies in the fact that Jesus draws man’s natural will away from opposition and back toward synergy, and in so doing he restores man’s true greatness. In Jesus’ natural human will, the sum total of human nature’s resistance to God is, as it were, present within Jesus himself. The obstinacy of us all, the whole of our opposition to God is present, and in his struggle, Jesus elevates our recalcitrant nature to become its real self.” (pg. 161).