Evil Men Are Closer to God Than We Think: Reflections on Divine Mercy

Two-thousand years removed from the death of Our Lord on Calvary, it is befitting to refresh our familiarity with the Passion narratives to see how Christ has chosen to extend, and relive, his sacrifice into our own times. The naked eye is apt to miss the genius, and purposefulness, behind every detail when we survey the Crucifixion only from surface level. The Good Shepherd makes clear to his disciples, “I lay down my life, that I may take it again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord” (Jn 10:17-18). Therefore, each detail relayed to us by the Gospel writers is without coincidence, and a telling of a story that is not merely a historical account of some past event, but the unfolding of an ongoing drama that is true in time eternal, for “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and for ever” (Heb 13:8).

Though Christ in his particular human body definitively died once on the hill in Calvary, he relives his sacrifice daily in his Mystical Body, through the manifestation of our flesh, in the exact same spiritual account as the one passed down to us in Scripture. Therefore, we ought not pass over a single detail to know how Our Lord lives among us today and gathers his flock to Himself.

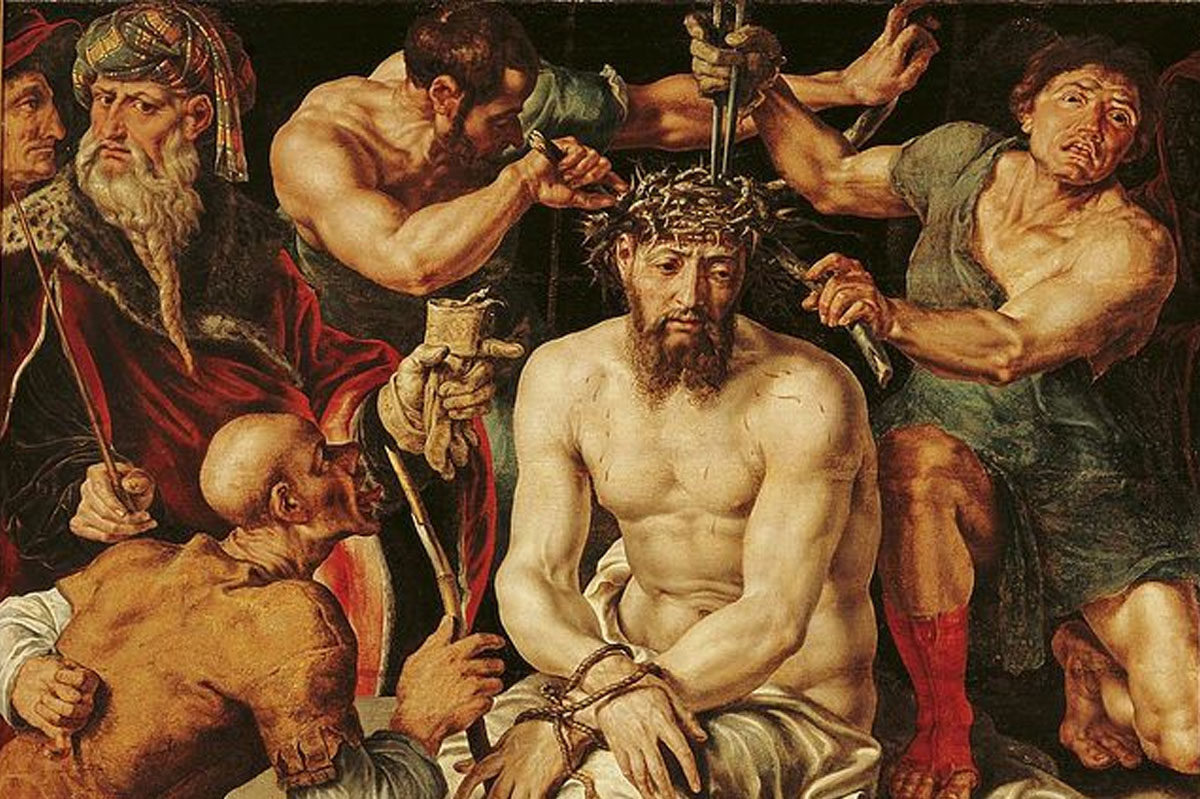

Since time immemorial, sin has drawn the ire of men. The Ven. Fulton J. Sheen writes in The Cries of Jesus From the Cross, “Since sin is the taking of divine life, it follows that nowhere else was sin better revealed than on Calvary, for there, sinful humanity crucified the Son of God in the flesh. Here sin comes to a burning focus. It manifests itself in its essence: the taking of Divine Life” (pg. 178). As such, all sin puts us at the scene of the crime. The question for us to ask two-thousand years later, then, is where do we all stand?

As Jesus Christ breathed his last, looked to Heaven, and said “It is finished” (Jn 19:30), who was there with Our Lord? There were, I would contend, three types of people. There were the really good, the really bad, and the repentant; those who heard God’s voice and listened, those who hated God and killed Him, and those sinners who looked with pity upon the Cross and saw the King take up his throne. Among the really good were the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Apostle John, and Mary Magdalene. The infant Church of then stands in place for the pilgrim Church today, who hears God’s word and keeps it. She receives the deposit of faith directly from our royal Majesty and obeys His command, which is love. The really bad need no exhaustive search to find. They are the executioners who snuffed out the light of the world. They stand for man as he is, in the state of sin. And finally, in the company of the repentant are the thief on the right and the centurion who stood there in front of Jesus. They are those who once were really bad but, having professed that “Surely this man was the Son of God!” (Mk 15:38), no longer want to be. They stand for the penitent today whom the really good, the Church, opens her arms to in love and forgiveness, as they hear the words, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise” (Lk 23:43).

These are the key players present at Our Lord’s death. Who, however, was amiss? Most noticeably, the eleven remaining Apostles, the crowd which placed palms at His feet days earlier, and the five-thousand fed by Christ by the Sea of Galilee. Not even those He raised from the dead were by Our Lord’s side on the day of His Crucifixion. He who handed him over to death, Judas, was awol. All but a few of Our Lord’s friends abandoned Him, and only the aforementioned cast was there on Calvary.

Knowing man’s heart and holding the antidote to his salvation, these events were no accident. The stars were deliberately aligned to achieve this, just as the cosmos announced Our Lord’s birth in Bethlehem. On the day of his Crucifixion, the executioners of Christ are closer to divinity than even Saint Peter, who was nowhere to be found. As we confront this reality, it ought to radically alter our perception of grace and put into perspective what Christ means when he says that “the tax collectors and the prostitutes are entering the kingdom of God ahead of you” (Mt 21:31). This image on Calvary also vivifies the words of Saint Paul to the Romans, as he writes, “where sin increased, grace abounded all the more” (Ro 5:20).

Is it possible that the most detestable among us whose sins receive the scorn of men are closer to Our Lord than even we? Is it their sins we detest, or does the depth of the evil they commit make us uncomfortable as it forces us to address the reality of sin and acknowledge our own? How often are we, who break bread with the Lord on Thursday and run to His empty tomb on Sunday, nowhere to be found on Friday? Why is it that God’s assassins are with him but not His friends?

Their closeness to God is no reason to despair, however, but the greatest reason to hope. Their hope is our hope. Jesus, speaking to Saint Faustina of His Divine Mercy, told her, “The greater the sinner, the greater the right he has to My mercy.” Never write off a sinner as hopeless, then. The killers of Christ are always within a closer reach of the divine than His friends. “What man of you, having a hundred sheep, if he has lost one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness, and go after the one which is lost, until he finds it?” (Lk 15:4). Perhaps the reason so many saints throughout the ages have suffered intense spiritual desolations is because Our Lord left their presence to console those in greater need of His mercy.

Those of us who frequent the sacramental life of the Church ought not to take our friendship with Christ for granted and think any higher of ourselves because of it. For even though on Thursday we tell Christ “I will lay down my life for you” (Jn 13:37) and “I will never fall away” (Mt 26:33), we deny Him three times and flee His side the very next day. In a stroke of divine genius, every sinner finds himself in the shoes of the executioners and within the reach of God’s mercy, since, as the Ven. Fulton Sheen says, all sin is “the taking of Divine Life.”

Anticipating our absence from Calvary on Good Friday, Our Lord instituted His Eucharistic sacrifice the night earlier, so those He knew would fall away might have a way back. Even though Peter and the ten others departed from Our Lord, Our Lord, beyond the scope of space and time, remained with them via their reception of His Body and Blood on Holy Thursday. The feeling of God’s distance from us, truly, is a share in Christ’s forsakenness on the Cross. Though the senses intuit a distance between us and divinity, He could never be closer, for He dwells within and makes his abode in the depths of our soul.

Only when we are close enough to be showered by the Blood and Water to pour from His pierced side do we receive God’s life in us. To get this close to Christ, we must confess that we too are the executioners. I am no better than he whose sins I perceive to be worse than my own! Perhaps, as he drives the nails into Our Lord’s hands and feet, I am nowhere to be found on Calvary while he has been blessed with Christ’s touch. Perhaps he is closer to God than me. And I pray he is, for his hope is mine. “Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord! So then, I of myself serve the law of God with my mind, but with my flesh I serve the law of sin.” (Ro 7:24-25).

Concluding that the good thief’s hope is our hope, Fulton Sheen writes, “May it not be that the conversion of the good thief is the key to the conversion of the modern world? Men will return to God, not because they are good, but because they recognize that they are evil. They will come to God through evil rather than through goodness. Or shall we say they will come to God through the devil. Countless are the instances in the Gospel of those who came to God after Satan was driven from their souls” (The Cries of Jesus From the Cross, pg. 97). May we pray for the conversion of the good thieves and that God may have mercy on us, for we know not what we do.